|

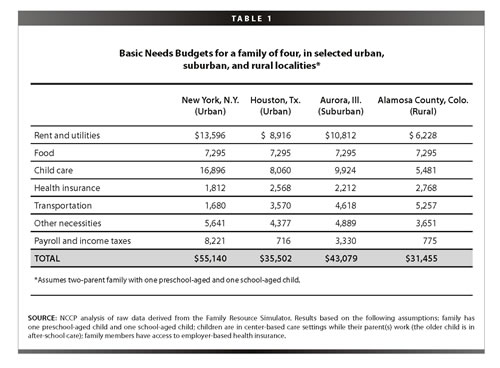

October 2, 2007 | EPI Briefing Paper #198 Improving Work SupportsClosing the financial gap for low-wage workers and their familiesby Nancy K. Cauthen Download print-friendly PDF version Low-wage workers and their families face rising levels of economic insecurity. Analysts estimate that anywhere from a quarter to a third of U.S. workers—35 to 46 million—hold low-wage jobs that provide few prospects for advancement and wage growth.1 Further, such jobs typically offer few of the employer-sponsored benefits—such as health insurance, paid sick leave, retirement plans, and the flexibility to deal with family needs—that higher-income workers often take for granted. At the same time, the costs of supporting a family—housing, medical care, child care, and transportation—have increased, consuming larger portions of the family budget. Increasing gaps between family income and basic expenses combined with easy access to expensive credit have conspired to saddle millions of working Americans with crippling debt. In short, low wages, few employer-provided benefits, few routes to advancement, the increased costs of basic necessities, minimal savings, and increased debt have left large numbers of American workers and their families economically vulnerable. Many such families are merely one crisis—a serious illness, job loss, or divorce—away from financial devastation. Government “work support” benefits—such as earned income tax credits, child care assistance, public health insurance coverage, and housing assistance—can help low-wage workers close the gap between insufficient earnings and basic expenses. And there is now abundant research evidence that work supports positively affect employment outcomes and family incomes, which in turn benefit children.2 For example, a series of expansions in the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) has been credited with contributing to an increase in employment and decrease in poverty among single-mother families from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s. Spending on work supports increased substantially in the 1990s, especially in the period following the 1996 federal welfare reforms that emphasized moving recipients to employment. Still, few families and individuals receive the work support benefits for which they are eligible. For example, the majority of workers who claim the federal EITC or obtain health insurance for their children do not receive other critical forms of assistance, such as help with child care or housing.3 Despite funding increases, overall spending levels continue to pale in comparison to what is needed to provide a comprehensive work support system for low-wage workers. Inadequate funding is largely a function of a lack of political will. But there are structural problems with the funding mechanisms as well—fixed block grants to states and state matching requirements constrain how much can be spent. For instance, when the economy declines, demand for work support benefits may increase, placing increased demand on state resources at a time when states are cutting spending. Other factors constrain access to work support benefits. Most of these programs were originally designed to provide a safety net for the poorest Americans, many of whom had little attachment to the labor force. Reforms in the late 1980s and 1990s sought to uncouple eligibility for public health insurance, and later child care assistance, from cash assistance. Those reforms were enormously helpful, but they have not gone far enough. In some states, work supports are still accessed primarily through welfare offices and are stigmatizing. Most benefits were designed to assist single mothers and their children; there are few benefits available to non-custodial parents and low-wage workers without children. Further, existing work supports suffer from burdensome application procedures, complex rules and delivery systems, and lack of coordination. But even the families fortunate enough to receive the multiple benefits for which they are eligible face another set of challenges. Eligibility levels are typically low and families lose benefits before they can get by on earnings alone. In some cases, just a small increase in earnings leads to the complete termination of a benefit (e.g., child care subsidies and health insurance)—the family faces a “cliff” and ends up financially worse off despite earning more. If we agree as a nation that full-time workers should be able to meet their basic needs and those of their children, we need a comprehensive, integrated work support system that is explicitly designed to address the challenges faced by ever-growing numbers of America’s workers and their families. U.S. work support programs need to be modernized and systematically overhauled. This paper begins by describing why work support programs are needed. It then goes on to explain the state of current U.S. programs and why we need to reform them. The final sections of the paper describe some concrete policy proposals for reform and offer recommendations about priorities and next steps. What are “work supports,” and why are they needed?What it takes to make ends meet In 2006, about one in four workers in the United States held a job that paid less than $10 an hour.4 If both parents in a family of four work full time (40 hours per week, year round) at the newly increased federal minimum wage of $5.85 an hour, their total annual earnings will be about $24,000 a year—the federal poverty line for a family of four is $20,650. But nowhere in the country can a family meet their basic needs on poverty-level earnings; the poverty level is widely acknowledged to be inadequate as a measure of financial need.5 In fact, research indicates that across the country, families typically need an income of about twice the official poverty level—or roughly $41,000 for a family of four—to meet basic needs. In a high-cost city like New York, the figure is up toward $60,000, whereas in rural areas, the figure is typically in the low $30,000s (see Table 1).6

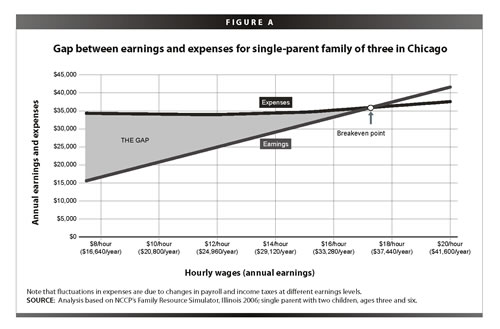

These figures are based on the National Center for Children in Poverty’s (NCCP) Basic Needs Budgets which include only the most basic daily living expenses. For example, although they include the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance premiums, they do not include out-of-pocket expenses for copayments and deductibles, which can be quite costly, particularly for families with extensive health care needs. The budgets do not include money to purchase life or disability insurance or to create a rainy-day fund that would help a family withstand a job loss or other financial crisis. Nor do they allow for investments in a family’s future financial success, such as savings to buy a home or for a child’s education. In short, these budgets indicate what it takes for a family to cover the most basic of living expenses—enough to get by but not enough to get ahead. Two parents each working full time at $10 an hour would together earn $41,600 and might be able to squeak by. But what about two-parent families in which the parents earn less than $10 an hour or one parent is unemployed or underemployed? What about the single parent who is solely responsible for providing for her children? Consider a single mother with two children living in Chicago. To make ends meet, she needs to earn about $36,000 a year, that is, $17 an hour at a full-time job.7 Figure A illustrates the gap between her earnings and her family’s basic expenses at lower hourly wages. If she earns $8 an hour—which is more than the minimum wage in any state—her family faces an $18,000 annual gap between earnings and expenses.

Faced with such a gap, working parents must make tough choices. Should they seek cheaper, but potentially less enriching, unreliable, or even unsafe care for their children? Double up with another family or live in an unsafe neighborhood to reduce the rent? Allow their family to go hungry at the end of the month? Or go without health insurance and hope that no one gets sick or injured? Using 200% of the federal poverty line as a proxy for what it takes to make ends meet, 39% of children in the United States live in families that face these kinds of choices.8 Work supports help close the gap between low earnings and basic expenses To assist low-wage workers, especially those with children, the federal and state governments offer a set of means-tested “work support” benefits that either supplement low earnings or reduce expenses by subsidizing the cost of needed goods or services. The work supports discussed in this paper include:

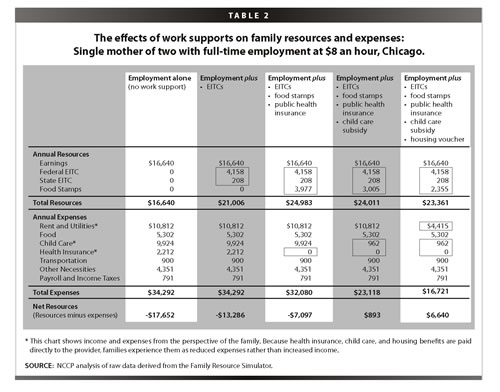

Table 2 illustrates the difference that work supports can make in helping a family close the gap between low earnings and basic expenses. It continues the example above: a single mother with two young children living in Chicago; the mother works full time at $8 an hour.

With a full-time job at $8 an hour, the mother’s annual earnings are $16,640. Without work support benefits, the family experiences an annual deficit of $17,652 after paying for basic expenses. If she claims both the federal and Illinois earned income tax credits, and her family receives food stamps and health insurance coverage, the deficit is reduced to $7,097. Only with the addition of a child care subsidy would she have sufficient resources to meet her family’s basic needs. A housing voucher would provide her with a surplus that would allow her to put some money into savings—for a car, a house, or her children’s education—or to pay off credit card, medical, or other debt. Although this example illustrates the critical difference that work supports can make for low-earning families, it is, of course, hypothetical. Very few families receive all the benefits for which they are financially eligible (also, benefits in Illinois are more generous than those in many other states). As this paper will detail, many aspects of existing work support programs—how they are structured, funded, and administered—are flawed and could be vastly improved. Nonetheless, work supports provide a promising policy mechanism for easing the financial strains faced by the rising numbers of families who are economically insecure, despite full-time employment. The effectiveness of work supports There is considerable research about the positive effects of work supports on family income and employment. Research on the federal EITC shows that it lifts more children out of poverty than any other government program. In 2003, the EITC lifted 4.4 million people—more than half of them children—out of poverty, reducing the child poverty rate by nearly a quarter.9 In many states, this impact has been enhanced by refundable state EITCs built on the federal credit.10 The EITC’s most striking employment findings are for single mothers. Research shows that the EITC contributed significantly to single mothers’ increased employment rates during the mid-1980s and late 1990s. Between 1984 and 1996, for example, labor force participation rates among single mothers increased from 73% to 82%, with more than 60% of this increase attributed to expansions in the EITC.11 Research also finds that the EITC has had strong employment incentive effects among cash assistance recipients.12 Another factor contributing to single mothers’ increased labor force participation during the 1980s and 1990s was the expansion in eligibility limits for public health insurance, particularly for children and pregnant women. Research indicates that when states increased income limits for health insurance beyond the limits for cash assistance, employment levels increased and welfare receipt declined.13 Public health insurance has also been shown to improve the health of millions of parents and their children by making preventive and primary care more readily available, and by protecting against and providing care for serious diseases14—and good health is associated with higher rates of employment and employment stability. Child care assistance has been found to have similarly positive impacts on employment outcomes. Research indicates that low-income mothers who receive child care subsidies are more likely to be employed, to work more hours, and to work standard schedules, as compared to low-income mothers without subsidies. Child care subsidy receipt is also associated with greater employment stability and higher earnings, especially for women without a high school degree and for single mothers.15 Research conducted in the wake of welfare reform suggested that housing vouchers can help families leave cash assistance, succeed in the workplace, and remain off the welfare rolls—and that work incentives such as earned income disregards and earnings supplements are more effective when recipients have housing assistance.16 There is also some evidence that the impact of vouchers on employment outcomes can be enhanced if vouchers are accompanied by efforts to encourage recipients to move to areas with lower poverty, better transportation, and more employment opportunities.17 Finally, adequate transportation is critical for getting people to and from work. Nearly 90% of American workers commute by car, and research shows that people with cars are more likely to work, to work more hours, and to have higher earnings.18 Two studies surveying welfare recipients in particular found that car ownership significantly increased the probability of finding a job and being employed,19 and while the evidence is limited, research suggests that promoting car ownership can have a substantial impact. A small subsidized car ownership program in Vermont found significant impacts on both employment and income among individuals transitioning from welfare to work and other low-income workers. Participants’ earnings more than doubled, and results indicated that for welfare recipients, the cost of the program was offset within months by savings in cash assistance benefits.20 The state of work supports in the United StatesThis section provides a brief description of each work support program:

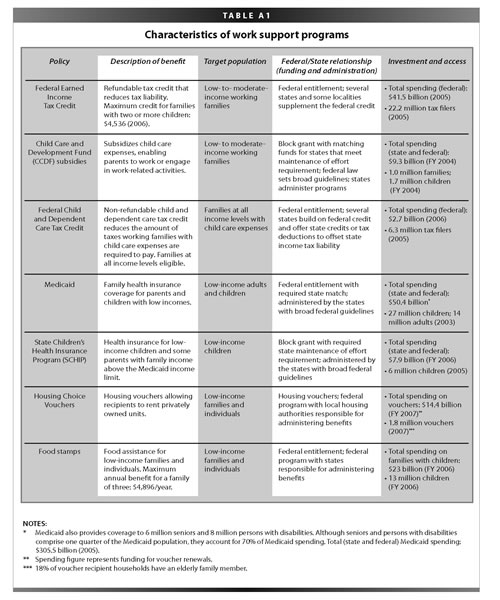

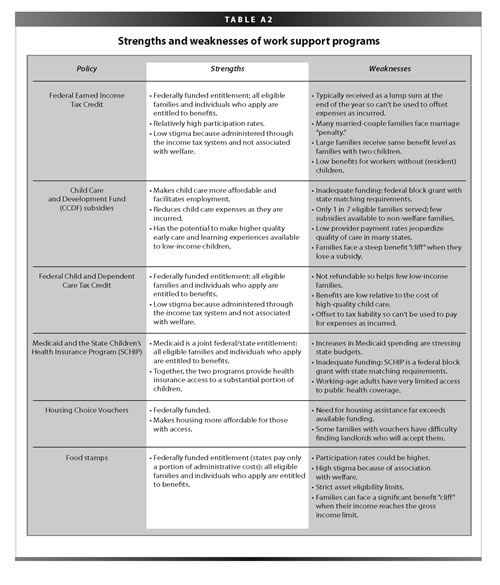

The purpose of this section is twofold. First, it provides some basic information about each policy: the nature of the benefit it provides (e.g., tax credit, a subsidy), eligibility requirements, funding and administration arrangements (detailing federal and state responsibilities), and other relevant information for understanding the current status of each program (such as the effects of welfare reform in 1996). Second, it highlights the strengths and weaknesses of individual programs. See Tables A1 and A2 in the appendix for summaries of some of this information. Earned income tax credits The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) reduces the income tax liabilities of low- to moderate-income working families—that is, families with annual incomes of up to about $38,000—and serves as a wage supplement. Since the EITC is refundable, any amount of the credit that exceeds a family’s tax liability is received as a cash payment. By definition, only families with earnings are eligible for the benefit. For tax year 2006, the maximum credit for families with two or more children was $4,536. For such families, the credit phases in at a rate of 40%, meaning that every dollar of earnings yields a 40 cent credit. The EITC reaches the maximum benefit level once families have $11,300 in earnings. At this point, additional earnings do not increase the amount of the credit. For married-parent families, the credit begins to phase out at $16,810 in earnings; the benefit decreases at a rate of about 21 cents per dollar of earnings until it reaches $0 for families with incomes greater than $38,348 (see Figure B).21 Benefits are slightly lower for single-parent families. The maximum benefit for families with one child was $2,747 for 2006. The EITC has the highest participation rate of all work support programs: it has been estimated that 80% to 90% of eligible families and individuals receive the credit, although filing rates are lower for individuals without children (who are eligible for much smaller benefits) and some evidence suggests that filing rates may be lower for former welfare recipients transitioning to employment.22 The EITC has been criticized for “penalizing” marriage (i.e., providing larger benefits to unmarried couples than to similarly situated married couples), not providing enough relief for families with more than two children, and offering minimal assistance to non-custodial parents (especially those with child support orders) and to workers without children.23 In stark contrast to an EITC benefit of 40% of initial earnings for families with two or more children and 34% for families with one child, workers without (resident) children receive only a 7.65% tax credit on initial earnings; the maximum benefit for 2006 was $412. In addition to the federal EITC, 18 states and the District of Columbia offer state-level credits, although in five of these states, the credit is not refundable.24 Nonrefundable credits offset the state income tax burden for some families but provide no benefits to families whose incomes are too low to owe state income tax. Child care assistance For many low-income working families, child care is by far their largest work-related expense. A 2005 survey showed that in every region of the United States, average fees for infant care in a center-based setting are higher than families’ average food expenditures, and in 49 states, the cost of center care for two children exceeds the median rent.25 There are currently two major child care assistance programs: subsidies provided through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) block grant and federal and state tax credits. Child care subsidies Child care subsidies pay providers directly for child care services provided to low-income families, and parents are required to make co-payments as earnings increase. Although some states have state-specific child care subsidy programs, all states participate in the federal-state CCDF program. The CCDF block grant was created by the same welfare reform legislation that created Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) in 1996. Over the next few years, spending on child care assistance increased substantially, but in recent years funding for child care subsidies has declined. Within broad federal guidelines, states define their own eligibility criteria, family co-payment levels, provider payment rates, and service priorities. Federal law sets the maximum eligibility level for CCDF subsidies at 85% of the state median income. Eligibility levels across the states for a family of three ranged from $18,000 in maximum annual income to more than $40,000 in fiscal year 2006.26 Because states are not required to serve all eligible families, these eligibility limits reveal little about the families who actually receive subsidies. In 2006, approximately one-third of the states had waiting lists or frozen intake for child care subsidies, including most of the country’s most populated states.27 Many of these states prioritize cash assistance recipients and those transitioning to employment for subsidy receipt. This means that the low-income working families least likely to receive child care subsidies are those who have never received cash assistance. One of the biggest problems with the child care subsidy program is that only a fraction of eligible families receive assistance—the best available estimate is that one out of seven families eligible for a subsidy under federal guidelines actually receives one.28 One reason (others are discussed later) is that there has never been a substantial federal commitment in the United States to provide parents with child care assistance, largely for ideological reasons. Children are considered primarily the responsibility of their parents; compared to many other countries, there is relatively little sense of societal responsibility to assist parents with the cost of raising children or to ensure their well-being. Operationally, this has meant that the federal government has stepped in to provide child care funds primarily for families receiving cash assistance so single welfare mothers could engage in work-related activities. Since CCDF subsidies are funded with a fixed federal block grant, it means that child care funding does not expand when demand increases. The funding structure requires states to provide matching funds, which can place additional constraints on funding. Other consequences of inadequate funding are low provider payment rates and high family copayments.29 When states pay low rates to child care providers, they may jeopardize the quality and reliability of available subsidized care. Further, the structure of child care subsidy programs is such that families typically cannot afford the full cost of care when their incomes exceed the eligibility limit (see the discussion of benefit “cliffs” in the next section). The loss of a subsidy sometimes requires families to move their children into cheaper—and potentially lower-quality, less-safe, and less-reliable care. Yet research is clear that high-quality early care experiences are one of the most promising mechanisms for bridging the achievement gap between low-income children and their more affluent peers.30 Child care tax credits The federal Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) reduces the amount of taxes working families with child care expenses are required to pay. It is the second largest source of federal child care assistance, and families at all income levels are eligible for the credit. To be eligible, a family must incur expenses for the care of a child under the age of 13 (or of an older dependent who is unable to care for him or herself) in order to work or look for work. In 2006, families with two or more children could claim up to $6,000 in annual child care expenses, and families with one child could claim up to $3,000. The credit equals 20% to 35% of the amount claimed, depending on family income. Since the credit is not refundable, its value to low-income families is limited. The credit cannot exceed what a family owes in taxes, and no benefit is provided to families whose incomes are so low that they do not pay taxes. The federal income tax threshold for a single-parent family with two children is about $15,000 per year. Such a family would not benefit from the CDCTC until the parent earned more than $21,000. Families with incomes under $20,000 receive less than 1% of the credit’s benefits—two-thirds of which go to families with incomes over $50,000.31 Although the maximum credit for families with two or more children is (at least in theory) $2,100, but no one actually receives that amount because of the way the child care credit interacts with other tax provisions. In 2005, the average benefit was only $52932—a fraction of what it costs to pay for full-time care for one preschooler in most parts of the country.33 Many states have built on the federal child and dependent care tax credit and offer state credits (or in some cases, tax deductions) to offset state income tax liability. Unlike the federal credit, 13 of the state credits are refundable.34 Other programs Although outside the scope of this paper, it is important to acknowledge that early care and learning programs such as Head Start and Early Head Start (which are federally funded) and state-funded pre-kindergarten programs can help provide care for children while their parents work. But these programs are often only a few hours a day, are rarely available year round, and demand far exceeds existing funding and capacity. Public health insurance Two major federal-state policies subsidize health insurance for low-income children and families: Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). Until the 1996 welfare reforms, Medicaid provided health insurance coverage primarily to families receiving cash assistance; most other low-income families were ineligible. The 1996 welfare reform law, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (PRWORA), “delinked” welfare receipt and Medicaid coverage for families. The goal was to base Medicaid eligibility on income rather than welfare receipt so that families would not seek cash assistance, or fail to transition off of the program, just to have health insurance coverage. SCHIP was created in 1997 to provide a federal incentive to states to extend health insurance to children living in families with incomes above Medicaid eligibility limits.36 States can cover the parents of children eligible for SCHIP only through a waiver process.37 Since SCHIP must be reauthorized in 2007, some changes in the program are likely. As a result of Medicaid expansions and the implementation of SCHIP, eligibility for public health insurance for non-immigrant children has dramatically increased. Most states now provide health insurance coverage for children with family incomes up to 200% of poverty—and several states have limits at or above 300% of poverty. But parents’ eligibility for Medicaid has lagged far behind. Only 13 states provide Medicaid coverage to parents with incomes equal to or greater than the poverty line.38 Despite significant expansions in eligibility for public coverage, access to health insurance is a significant and growing problem for children and parents at all income levels—in part because of rapid declines in access to employer-based coverage. In 2005, for the first time in nearly a decade, the number of children in the United States who lack health insurance increased. Given another increase in 2006, nearly 12% of America’s children are uninsured, including almost 20% of low-income children.39 And access to health insurance coverage for low-income working-age adults is extraordinarily limited—just 16 states cover parents with income up to the poverty level, a decline from 20 states in 2002.40 Housing assistance Federal Housing Choice Vouchers (sometimes referred to as Section 8 vouchers) and public housing units are the principal federal housing subsidies that directly benefit low-income families. The trend over time has been away from providing individuals with publicly owned units to subsidizing rentals in the private market. Currently there are just over 1 million households living in public housing units, and about 2 million who receive housing vouchers. The remainder of this paper focuses only on vouchers.41 Unlike other work supports discussed here, housing vouchers are federal-local—that is, federal funding is distributed directly to local public housing authorities, which administer the voucher programs. Recipients rent privately owned units, and vouchers allow recipients to live anywhere with rent at or below the local “fair market rent,” estimated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), as long as the landlord is willing to accept vouchers. Recipients can also live in units with rents above the fair market value if they are willing to pay the difference.42 Eligibility limits are based on a percentage of the local median income. In general, applicants’ income must be below 50% of the local median for their family size,43 and 75% of new voucher recipients each year much have income below 30% of the area median. Typically, recipients of housing subsidies are required to pay 30% of net household income (after deductions) for rent. This means that each additional dollar of earnings results in a 30-cent increase in rent, leaving a net income gain of 70 cents.44 Because the number of families eligible for housing vouchers is many times larger than the number of subsidies available, most applicants, especially in urban areas, are placed on a waiting list when they apply; and in some places, the waiting lists are closed.45 Like child care subsidies, one of the biggest weaknesses of the voucher program is that it assists so few families relative to demand. Food stamps The federal Food Stamp Program is federally financed, except for administrative costs, which are borne by state and local governments. States administer the program, generally through local welfare agencies, although this has become more variable over time. Most of the eligibility criteria are established by the federal government, but states are permitted to exercise limited options with respect to eligibility and benefit calculations, especially with regard to cash assistance recipients. States also have a number of administrative options. Food stamp eligibility is based on citizenship, income, and asset tests. The 1996 PRWORA legislation changed food stamp eligibility so that most legal immigrants no longer qualify for benefits, though some of these restrictions were later repealed.46 To be eligible, gross family income must be no more than 130% of the federal poverty line, and net income (after deductions) must be no more than 100% of the poverty line. Liquid assets must also be minimal. Households (without an elderly member) are limited to $2,000 in counted liquid assets. A portion of the value of family vehicles—generally the “fair market value” above $4,650—is counted in calculating assets. Households comprised entirely of cash assistance recipients (in TANF, Supplemental Security Income, or general assistance) are automatically eligible for food stamps, and thus exempt from the gross income and asset tests. Recipients not caring for a child under age six or a disabled family member are subject to work-related requirements. There are also stringent work requirements and time limits for able-bodied adults without dependents. Benefit levels are based on family size and net income (after deductions). In fiscal year 2005, the average monthly benefit was $213.47 Given that food stamps are largely federally funded, states have an incentive to enroll eligible families and individuals, yet the participation rate is only about 65 %.48 More than most work support benefits, food stamps probably retain more of a welfare-related stigma than other programs discussed here. Transportation There is very little federally funded transportation assistance for low-income families. In the wake of welfare reform, the federal Job Access and Reverse Commute (JARC) program was created to help low-income individuals access jobs and facilitate the transition from welfare to work. A 1998 study by the GAO found that while three-quarters of welfare recipients lived in central cities or rural areas, two-thirds of new jobs were in the suburbs.49 JARC provides grants to states and communities that can be used for a variety of locally determined purposes, including bus or van services, car ownership assistance programs, and efforts to expand public transit. For fiscal year 2007, the federal government authorized $144 million for JARC; grantees also contribute matching funds.50 In addition, about one percent of TANF funding is used to assist recipients with the cost of employment-related transportation costs. Most other transportation initiatives to assist low-income families and individuals are funded by states and localities. How could current work support programs be improved?Given that a quarter to a third of U.S. jobs pay low wages—and that evidence suggests this trend will continue, if not worsen—a comprehensive public work support system could help millions of working families narrow the gap between earnings and their most basic expenses. It could also help to bridge the widening gap between families and individuals at the bottom of the income scale and those at the top. To lay the groundwork for a discussion of recommended reforms, this section discusses limitations regarding program structure and funding arrangements that cut across programs. (See box on p.14 for a discussion of implementation barriers to program access.) Program structure: phase-out rates, cliffs, marginal tax rates Since work supports are designed to help workers with low wages, they are means-tested: as earnings increase—particularly as they rise above the official poverty level—benefits typically begin to phase out until the recipient reaches the income eligibility limit, at which point the benefit is completely terminated. The purpose of means testing is to target benefits to those who need them most and to contain program costs. But means testing can have unintended consequences for a family’s financial bottom line when benefits are terminated abruptly. For example, when an individual or family reaches the income eligibility limit for public health insurance, an additional dollar of earnings results in the complete termination of coverage. In other words, the recipient faces a “cliff”—a point at which a small increase in earnings results in substantial benefit loss. Food stamp benefits are gradually reduced as earnings increase, but recipients eventually face a cliff. For example, an additional $500 in yearly earnings, from $19,500 to $20,000, can lead a family to lose $2,000 to $3,000 a year in food stamps. Likewise, in some subsidized child care programs, there is a gradual increase in co-payments and then a complete termination of benefits when the family reaches an eligibility limit, which typically forces families to switch to cheaper care. In addition to benefit loss, increased earnings may also lead to an increase in work-related expenses, such as higher income taxes. The combination of rising taxes and the loss of work supports means that extra earnings don’t always improve a family’s financial bottom line. In the worst-case scenario, a family ends up with less despite increased earnings. Let us return to the example of our single-parent family of three in Chicago and assume that the family receives federal and state earned income tax credits, a child care subsidy, public health insurance, and food stamps. Figure C shows that the family can make ends meet with the parent’s full-time job at $8 an hour and work supports (note that this is not common; Illinois’ work support programs are relatively generous). If the parent’s earnings increase to $10 an hour, the family loses its food stamps and faces a cliff, i.e., a financial loss. At just over $14 an hour, the family faces a much steeper cliff when losing its child care subsidy. The family not only sustains a huge financial blow; it is actually slightly worse off than when the parent earned only $8 an hour. (Because eligibility and benefit levels for many work support programs are set by the states, the exact patterns and effects of benefit loss vary from state to state and sometimes within an individual state.) The financial impact of a benefit loss on a family is largely a function of how gradually (or abruptly) the benefit phases out. The federal EITC, for example, phases out quite gradually: from a maximum benefit of $4,536, the credit decreases at a rate of about 21 cents per dollar of earnings, until the benefit reaches $0. Therefore, an extra dollar in earnings leads to a loss of 21 cents of the credit—or a “marginal tax rate” of 21%. Of course, since the phase-out rules for each program are designed independently of other programs, they can have a cumulative effect far more severe than policy makers might have intended. For example, if three benefits each phase out at a rate of 30 cents per dollar of earnings, the cumulative effect could be that an additional dollar of earnings results in a loss of 90 cents in benefits. Although the impact of benefit loss may be less severe if a family is not receiving multiple benefits, the issue of these aggregate effects will become increasingly important as efforts to promote participation in work support programs continue and more families receive the benefits for which they are eligible. The key decision for policy makers and analysts is to determine what levels of marginal tax rates are optimal. Policy makers should be most concerned about marginal tax rates that exceed 100%: earning more should always leave a worker better off. Low to moderate marginal tax rates provide a way to target the highest benefits to those in greatest need of assistance, while still retaining a strong incentive for workers to earn more. Funding arrangements: constraints and uncertainties Current work support programs are characterized by wide-ranging funding arrangements (see Table A1 in the appendix). The critical variables are:

The effectiveness of work support programs is constrained by two aspects of current funding arrangements: (1) overall funding levels are inadequate, and (2) reliance on state funding creates uncertainty during periods of economic downturn. Current funding levels have greatly constrained the proportion of families and individuals eligible for work supports who actually receive them. As mentioned above, coverage rates for many benefits are quite low, especially for child care and housing subsidies. Even though Medicaid is an entitlement, roughly a third of eligible individuals do not receive benefits. Medicaid is one of the largest—and fastest growing—state-level expenditures, so states have an incentive to control enrollment.51 A second constraint on work support spending is that state governments do not have the same capacity as the federal government to run budget deficits. During economic downturns, when revenues are down and demands on the state budget increase, programs for low-income families and individuals are often the first to be cut—even in the face of greater demand for benefits. States may deal with budget pressures by either lowering eligibility limits or reducing benefits—or both. During the 1990s, for example, funding for child care subsidies and health care benefits for children was greatly increased. But the trend has not continued since 2000. Only 15 states, for example, provide access to both children’s health insurance and child care subsidies for families with earnings at 200% of the poverty level—and in several of these states, eligible families face waiting lists for child care assistance.52 From 2001 to 2006, eligibility limits for child care subsidies fell as a percent of poverty in more than two-thirds of the states. Many states also increased family copayments during this period, and the number of states with adequate reimbursement rates for providers declined from 22 to just nine.53 Finally, due to limited funding, an estimated 250,000 children have lost assistance since 200054—a year when only an estimated one in seven eligible children was being served.55

Proposals for changeThis section outlines a series of proposals that address some of the most serious limitations of current programs and extend access to work supports to families and individuals at higher income levels. These proposals are intended to lay the groundwork for more comprehensive reforms over time. The recommendations are informed by the concept of “progressive universalism,” which refers to providing help to all while providing the greatest assistance to those in greatest need. For the work supports discussed below, the policy reforms recommended fall somewhere in between narrow means testing and true universalism, which provides something to everyone. Although there are certainly instances where universal programs are the best policy approach (e.g., public education), the point here is that progressively targeted programs also can be successful.58 (See Middle-income families need work supports? below for a rationale for including moderate-income families in at least some work support programs.)

Goals for a modernized work support system Before discussing concrete proposals, it is necessary to identify a set of goals that should guide the creation of a comprehensive work support system. The overarching goal is to extend work supports to all low- to moderate-income workers who need assistance, while better meeting the needs of the poorest working families, regardless of whether they are connected to the welfare system. 1. Full-time work, combined with public benefits, should be sufficient to cover a family’s basic expenses. Having a strong work ethic and working hard to support one’s family are widely shared values in this country, but the promise of hard work is belied by the growing percentage of workers who work full time and still cannot afford basic necessities. 2. Earning more should always improve a worker’s or family’s financial bottom line. Although phasing out benefits as earnings increase is an effective way to target benefits to those in greatest need, benefits should nonetheless be structured in ways that do not lead to “cliffs” and extremely high marginal tax rates. When workers work more and earn more, they should always be better off. 3. Funding for work supports should be structured to expand during economic downturns and adequate to ensure that all eligible applicants receive benefits. Too many work supports are under-funded and only the federal EITC and food stamps are fully federally funded as entitlements, which allows them to expand automatically to meet rising demand. 4. Work support programs should be efficiently administered and easily accessible to eligible families and individuals. To the degree that programs target the same families and individuals, they should be consolidated and/or coordinated and easily “packaged.” In terms of “friendly” implementation:

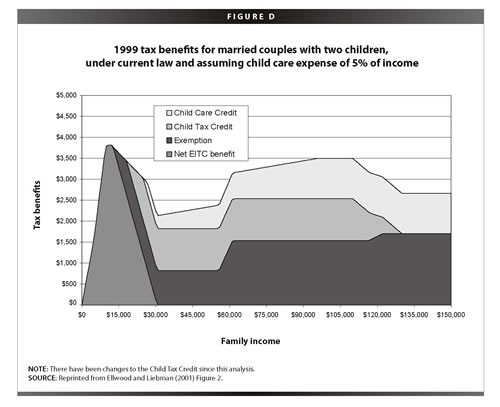

5. Work supports should help provide a bridge to the middle class. Benefit eligibility should expand to higher income levels so that workers can receive assistance (at least) until their earnings are sufficient to meet basic needs. Small amounts of assets should not preclude eligibility, and the system ought to provide opportunities for asset development. The proposals discussed below touch on most, but not all, of these principles (e.g., program implementation is not addressed). The recommendations cover federal income tax credits, child care subsidies, food stamps, and transportation. Although improving access to health insurance is vitally important to work support reform, other parts of the Economic Policy Institute’s Agenda for Shared Prosperity focus on this important issue. Proposal 1: Expand the federal Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit No single work support policy has received as much attention as the federal EITC. Given its proven ability to promote employment and reduce poverty—as well as the fact that as a tax credit, it is relatively stigma-free and easy to access—it is not surprising that so many proposals for assisting low-wage workers start with the EITC. Building on the work of Robert Cherry and Max Sawicky, an analysis by David Ellwood and Jeffrey Liebman shows that collectively the EITC, Child Tax Credit (CTC), the dependent exemption, and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) provide the highest benefits to very low- and higher-income families (Figure D).62 Low- to moderate-income families are disadvantaged because they earn too much to qualify for the EITC yet too little to reap the full benefits of non-refundable and partially refundable tax provisions pertaining to children. (Note that the CDCTC is discussed below with proposals regarding child care assistance.)

Unified family credits and improved benefits for workers without children To address the various criticisms of existing tax credits, a number of analysts have proposed versions of a “working families tax credit.”63 Although the specifics vary from proposal to proposal, common elements include combining the EITC, CTC, and dependent exemptions; further reducing marriage penalties; and increasing benefits for larger families. The current EITC provides only two benefit levels for families with children—one for families with one child and a second for families with two or more children. To reduce poverty among larger families, policy analysts have proposed adding a higher benefit tier for families with three or more children.64 In recent years, policy analysts also have stressed the importance of increasing EITC benefits for non-custodial parents and childless workers. Falling wages and declining job opportunities for low-skilled men, especially men of color, are believed to have exacerbated the trend toward childbearing outside of marriage and the prevalence of single-parent households.65 In stark contrast to an EITC benefit of 40% of initial earnings for families with two or more children and 34% for families with one child, workers without (resident) children receive only a 7.65% tax credit on initial earnings; the maximum benefit is just over $400. Increasing EITC benefits for non-custodial parents and childless workers would reward labor force participation and reduce poverty among these individuals with the potential to strengthen low-income families in the long run. Extending EITC benefits to younger workers without children (childless workers under age 25 are not currently eligible for the EITC) could have similar effects. In short, the key recommendations for comprehensive reform of the EITC and tax provisions relating to children include:

Specific proposals The long-term aim should be to consolidate the EITC, CTC, and dependent exemptions to make them function better together toward the goal of progressive targeting. But this kind of overhaul would be most effective in the context of a larger effort to simplify the income tax system. An interim step would be to adopt the recommendations of the Center for American Progress (CAP) Task Force on Poverty, which emphasize expanding the EITC and the CTC. Specifically, the Task Force recommends the following:66 Expand the EITC

Make the Child Tax Credit fully refundable

In addition to these reforms, benefits should phase out more gradually, both to reduce the marginal tax rates and also extend modest benefits into a higher income range. This would provide some payroll tax relief for moderate-income families. These issues are addressed by several of the proposals mentioned previously to create a unified working families tax credit. Estimated costs and other considerations A note about cost estimates: The estimates provided throughout this section are for individual proposals and do not reflect their interactive effects, nor potential cost savings. Any proposal that increases employment—whether by drawing new entrants into the labor force or increasing hours worked by current workers—would increase payroll and potentially other tax revenues. Of course, increased work effort would likely increase the demand for child care assistance. But making the CTC fully refundable would provide low-income families with more resources to spend on other needs—whether child care or something else. The point is that determining the costs of enacting multiple proposals requires an analysis of their interactions, but total costs would be significantly less than the sum of costs for individual reforms.CDI3Bu8ac The CAP Task Force on Poverty estimated that their proposed reforms for expanding the EITC would cost $22 billion a year and that making the CTC fully refundable would cost $13.6 billion a year. Proposal 2: Guarantee child care assistance for low- to moderate-income workers Child care is one of the most important work supports, yet arguably the weakest among current policies. Parents need safe and reliable care for their children so they can work. And children need high-quality, stable care to facilitate healthy development. For the most disadvantaged children, one of the most important investments we can make in their future is to ensure that they have early access to high-quality care. End, or bridge, the bifurcation between subsidies and tax credits Child care assistance is currently bifurcated between means-tested subsidies for low-income working families and a modest, non-refundable federal tax credit that primarily benefits middle- and upper-income families. In the long term, we should aim for a single system of federally funded child care provisions to assist families on a progressive basis. Our goal should be to support parental employment by assisting low- to moderate-income workers with the cost of child care and in ways that promote positive outcomes for children (e.g., by allowing families to purchase higher quality care). Assisting families of different income levels through different policy mechanisms perpetuates stereotypes—that poor people are different from everyone else, that they alone benefit from government “handouts,” and that government does little to help the middle class68—while dividing the political constituency for this all-important benefit. The best option is to provide child care subsidies on a sliding scale that extend through the middle-income range, while doing away with the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC). This is, of course, the most expensive option. But the CDCTC is not well targeted and arguably inefficient: because it is not refundable, the CDCTC does not provide much help to low-income families, yet it provides only very modest benefits to families who are more well off at a cost of roughly $10 billion a year. Another option would be to do away with subsidies and to provide all child care benefits through a tax credit. But tax credits, unlike subsidies, do not provide assistance as costs are incurred, which is a problem for low-income families. It might be possible to design provisions for advance payments, but this would add cost and complexity, greatly diminishing the simplicity that tax credits can offer. This option should be taken off the table. An interim option would be to optimize the existing child care subsidy program so that it serves a much greater percentage of families who are already eligible, while expanding and enhancing the federal CDCTC so that it provides meaningful relief to low- to moderate-income families with child care expenses. This option retains the bifurcation but provides a bridge between subsidies and tax credits. Finally, any child care proposal needs to address the current inequities in access to subsidies across states by setting minimum federal eligibility standards. Not only do state eligibility levels vary considerably, but between 2001 and 2006 half the states reduced their eligibility levels.69 We also need to address the volatility in subsidy funding by requiring the federal government to assume a greater share of the costs. Specific proposals Barbara Bergmann has developed a proposal that expands access to child care subsidies well into the middle-income range.70 It builds on the subsidy system and would replace the CDCTC. Here are some specifics: Expand access to child care subsidies into the middle class and eliminate the CDCTC

Bergman’s plan would benefit both low- and middle-income families. Since benefits are based on the cost of care, families with higher child care costs—whether because they have preschool-aged children, large families, or live in high-cost areas—would receive higher benefits. They would also be eligible for assistance at higher income levels. By gradually increasing co-payments, the plan would eliminate the cliff that families currently face when losing a subsidy. Bergmann recommends a co-payment rate of 20% because she takes into account the interactive effects with other work supports: as income increases, families are eligible for fewer EITC and food stamp benefits. Mark Greenberg, executive director of the CAP’s Task Force on Poverty, offers an alternative proposal that expands both the existing child care subsidy program as well the CDCTC.71 The proposal was subsequently adopted in the task force recommendations.72 The specific provisions of Greenberg’s proposals include: Provide a federal guarantee to child care subsidies for low-income families

Expand the child and dependent care tax credit

While retaining the bifurcation between subsidies and tax credits, Greenberg’s proposal provides a bridge between the two: families who hit the subsidy eligibility limit would still be eligible for a refundable tax credit, softening the cliff that families currently hit when losing a subsidy. Estimated costs and other considerations Bergmann estimates that her proposal would cost an additional $26 billion over what is already being spent (note that this estimate was derived a number of years ago). Her proposal includes a provision to increase child care quality by providing extra bonuses for higher-quality care. Greenberg estimates that his child care subsidy proposal would cost roughly an additional $18 billion a year over what is currently being spent ($11 billion in additional federal expenditures and $7 billion for the states).73 The reforms would increase access to child care subsidies to about 3 million low-income families, which would be a three-fold increase in recipients.74 His cost estimates also include funds for quality improvement. Researchers at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center estimate that making the CDCTC refundable and expanding the top rate of the credit to 50% would cost approximately $5 billion a year. They estimate that making the credit refundable would make the CDCTC available to an additional 1.5 million households (for a total of 7.9 million households).75 Due to different assumptions, methodologies, and timeframes, it is not possible to make direct comparisons between the proposals without further analysis. Bergmann’s proposal is better for the long run because it provides child care benefits via a single mechanism to all eligible families. Greenberg’s proposal might be more politically feasible in the short run. Note that both Bergmann and Greenberg correctly argue that the federal government needs to take the lead in funding child care to ensure greater access and to reduce the likelihood of benefit cuts during economic downturns. Proposal 3: Expand the federal Housing Choice Voucher Program and subsidize homeownership Policy makers need to be concerned both with housing affordability and also with neighborhood quality. It is not enough for low-income families to obtain affordable housing if that housing is located in neighborhoods that are unsafe, do not provide access to decent jobs for parents and quality schools for children, and do not have affordable grocery stores and other services. Having said that, the policy focus of this paper is housing affordability. Just as with child care, the provision of federal housing assistance is bifurcated between tax breaks for middle- and upper-income households and subsidies for low-income households. But in this case, housing assistance is further bifurcated—tax breaks favor homeownership, while subsidies for low-income families primarily subsidize rentals. I would argue that we should be less concerned about the bifurcation in the mechanisms for providing housing assistance to households of different income levels, and more concerned about the strong bias against homeownership for low-income families. Most importantly, funding levels for low-income housing assistance are terribly inadequate. Assist more families and subsidize homeownership—not just rentals Estimates of the numbers of families and individuals who are financially eligible for housing assistance (including vouchers as well as public housing) but who do not receive benefits vary from two-thirds to over three-quarters.76 Waiting lists for housing vouchers can be many years long, especially in urban areas, and are often closed to new applicants. Yet outside of urban centers, vouchers sometimes go unused, often because there are insufficient rentals with landlords who will accept subsidies. In other words, there is a geographic imbalance between available subsidies and demand, with some areas serving only a fraction of applicants and others having vouchers that go unused. This is no doubt related, at least in part, to bias in the voucher program against homeownership. Policy makers need to address two problems with the housing voucher program. The first and foremost problem is that funding is grossly inadequate. Currently, about 2 million families have housing vouchers (approximately 1 million more live in public housing). Despite evidence of increased need—the number of households who face “severe housing cost burdens” has increased substantially since 2000—the number of vouchers in use has actually declined and payment standards have been reduced.77 Meanwhile, average rental costs have increased. The second issue that needs to be addressed in the short run is the bias against homeownership in the voucher program. A quarter to a third of low-income families with children are homeowners. Existing legislation allows for housing vouchers to be used for homeownership, but public housing authorities have been slow to adopt the option because of administrative costs.78 Specific proposals Because housing is one of the largest budget items for low-income families, we should work to increase substantially the number of families aided by: (1) doubling—or even tripling—the number of vouchers in circulation, and (2) increasing incentives for public housing authorities to offer the homeownership option through the voucher program, in part by providing additional administrative funds to support start-up and implementation. One way to defray at least some of the cost of additional vouchers is by shifting the allocation of current federal housing assistance. Some evidence suggests that providing housing assistance directly to low-income families is more efficient than subsidizing the construction and rehabilitation of rental units for low-income households or providing subsidies to sellers of low- to moderate-income housing.79 A potentially more controversial way to shift the allocation of federal housing subsidies would be to place restrictions on the home mortgage interest deduction, which can be used not only for a family’s primary residence but also for a second home, for a maximum of $1 million in loans. Although this has not always been true, most of the tax advantages of the mortgage interest deduction now accrue to the affluent rather than struggling first-time homebuyers.81 In 2004, more than 55% of the mortgage tax subsidy benefited just 12% of taxpayers with incomes above $100,000. Estimated costs and other considerations Doubling or tripling the number of housing vouchers and providing incentives for using vouchers to promote home ownership would cost anywhere from $12 to $30 billion a year in additional expenditures. Although expensive, housing-related tax breaks (including both mortgage interest and property tax deductions) for middle- and upper-income households cost about $75 billion a year. Proposal 4: Eliminate the gross income and asset tests for food stamps The Food Stamp Program provides critical assistance to millions of low-income Americans, supplementing low wages and significantly reducing the incidence of hunger and food insecurity. But the program could be significantly improved as a work support by simplifying the eligibility requirements. Under current federal rules, most food stamp recipients must meet three financial tests: (1) an asset test (family assets may not exceed $2,00083), (2) a gross income test (total family income must be below 130% of the federal poverty level), and (3) a net income test (family income—after deductions for child care expenses, housing costs, and so on—must be below the poverty level). The gross income and asset tests can lead to significant benefit cliffs.84 Food stamp benefits decrease gradually as earnings increase—every additional dollar in income leads to a loss of approximately 30 cents worth of food stamps. But when a family’s gross income exceeds 130% of the poverty level—and it takes only an additional dollar of earnings to do so—the family loses its entire benefit. So, for example, families with high child care or housing costs may still qualify for $2,000 to $3,000 in food stamp benefits when they hit the gross income limit and become ineligible. Similarly, a small increase in savings to just above $2,000 leads to a full termination of benefits. Figure E illustrates how waiving the gross income test for food stamps would ease the cliff for the hypothetical family from Chicago discussed earlier in the paper. Under current federal food stamp rules, the gross income and asset tests do not apply to certain families, such as households in which all members receive TANF cash assistance or Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and there is a federal option that allows states to waive these tests for additional families. A dozen states have waived the gross income and asset tests for a substantial portion of food stamp recipients and some have effectively eliminated these tests altogether. Specific proposals In addition to recommending the elimination of the gross income and asset tests for food stamps, policy makers should also support proposals pending in Congress that would increase the standard deduction for households with one to three members—a number that has been frozen for well over a decade—and eliminate the cap on the child care deduction, so that families’ full child care costs would be deducted from their resources for the purpose of eligibility determination. Estimated costs and other considerations Eliminating the gross income and asset tests would smooth the cliffs and simultaneously make the Food Stamp Program easier to administer. Benefits would remain available only to families whose net income (after deductions) is below the federal poverty level. It is estimated that as a result of the current federal option—under which 12 states have eliminated these two eligibility requirements for many or all recipients—about 300,000 additional low-income people receive benefits, at a cost of about $148 million a year. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that a proposal by the Bush administration to eliminate the federal option in the fiscal year 2008 budget would save $740 million over the next five years.85 CBO estimated the cost of increasing the standard deduction for households with one to three members at $2.2 billion over five years and the cost of eliminating the cap on the child care deduction would be $249 million over five years.86 Proposal 5: Provide federal relief for transportation costs In most of the United States, car ownership is an unavoidable work-related expense, as owning a reliable vehicle is critical to getting a job and maintaining employment. Research demonstrates a strong association between car ownership and employment as well as earnings. Moreover, while there is currently little money devoted to transportation assistance, there is evidence that such programs can be quite effective.87 For the long term, we should deal with transportation assistance for low-income families within a broader policy context that emphasizes increased investments in public transit and decreased reliance on individual vehicles. Although such a policy discussion is desperately needed, low-income families need help now. Especially for those living in rural areas, private car ownership is likely to be the only reliable mode of transportation for quite some time. Nonetheless, subsidizing car ownership to support work in the short run might have unintended negative consequences for public transit88—finding the right balance presents a formidable policy challenge. Specific proposals Margy Waller, now director of the Mobility Agenda, offered a proposal in 2005 for a federal income tax credit that would help low-income workers afford a car and offset the cost of commuting for both low- and moderate-income workers.89 This credit would also be available to workers who commute by mass transit. More specifically, she proposed that the federal government:

Other steps that would help promote car ownership among low-income families include exempting vehicles from the food stamp asset test (or eliminating the asset test altogether, as recommended above) and increasing federal funding for car ownership assistance programs. Currently, such programs are generally small and supported largely by state and local funding.90 Waller argues that a commuter tax credit would make a substantial difference in low-income families’ ability to buy and maintain a reliable car, while only increasing the total number of vehicles on the road by about 3.5%. Although this proposal sounds promising, an impact analysis should be conducted to assess its effects on the use of public transit. Estimated costs and other considerations Waller estimates that if all eligible workers applied for the credit, the proposal would cost $100 billion a year—a figure she acknowledges that many would view as prohibitive. In fact, the estimated cost of this proposal is much higher than any other proposed here (although the estimate would clearly be less once adjusted for reasonable assumptions about participation). A commuter tax credit might need to be phased in gradually, with lower benefits at first, just as was done originally for the CTC. ConclusionImplementing the agenda recommended above would require a significant financial investment by the federal government, as well as a greater commitment on the part of the states. But the importance of building a comprehensive work support system should not be underestimated. In an era in which most high school graduates in the United States cannot command a living wage, and a huge proportion of new jobs created in the United States pay low wages and offer few benefits, policy makers need to heed the message—millions of Americans are working hard, yet not coming close to being able to make ends meet. Those of us concerned about the unmet needs of low-wage workers should move simultaneously on multiple fronts. First, we should fight for higher wages (other parts of EPI’s Agenda for Shared Prosperity address this issue). Over the last 25 or so years, our political discourse has increasingly emphasized personal responsibility. It is now time to restore the balance with calls for corporate and government responsibility—and accountability—as well. Second, we need to continue to promote higher education, technical and vocational training, and other skill-building efforts that would allow low-wage workers to command higher wages. And as we address wage growth and skill-building, we need a systematic effort, such as the one proposed in this paper, to reform work supports in a way that “makes ‘work supports’ work.”91 As with any major policy agenda, it is critical to set priorities. The most pressing challenges are to offset the costs of raising children and to provide health insurance (not only to children but to adults as well). Of the proposals listed above, two top priorities should be to make the child tax credit refundable and to expand access to child care assistance. Expanding the EITC should be a priority as well. Based on research evidence, these reforms offer the greatest potential in the immediate term for making real change in the lives of low-income workers and their families—especially their children. How would the nation pay for comprehensive work support reform? There are several factors to consider. First, this paper treats policy proposals independently of one another, but in the real world, they would have interactive effects that would reduce overall costs. Evidence clearly shows that subsidizing the cost of going to work increases work effort and therefore tax revenues. Moreover, if we address the need for affordable child care and health insurance, for example, families will have more resources to spend on housing and transportation. Assisting low-income families with housing would allow some workers to live closer to their jobs, reducing their transportation costs. And so on. The question of the true cost of meaningful work support reform is a legitimate one, and it must be addressed. But the question of “affordability” cannot be addressed in a vacuum. We must also ask: what are the costs of not addressing the needs of our nation’s lowest paid workers and their children—there is plenty of evidence that those costs are considerable.92 At the end of the day, the question of “what we can afford” in the wealthiest nation in the world comes down to a question of national priorities. I am grateful to my colleague Kinsey Dinan for her considerable input and feedback on this paper and also extend my thanks to Sarah Fass, Jessica Purmort, and especially to Jodie Briggs, for their helpful research assistance. Many thanks as well to Jared Bernstein and John Irons of EPI for their very thoughtful comments on earlier drafts. I alone am responsible for any shortcomings. Appendix

Endnotes

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||